Today is Madaraka Day, marking the June 1, 1963 rite of passage when Kenya gained internal self-government from the British colonial state.

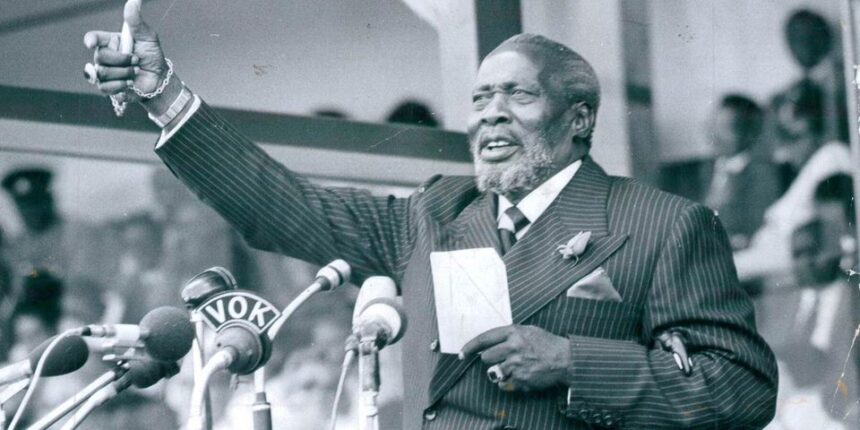

It went on to get full independence (at least on paper) on December 12, 1963. Jomo Kenyatta, then 66 (going by 1897 as his birth year), became the first Prime Minister and later President. At that age, Kenyatta was one of the oldest of the independence generation African leaders.

Among the leaders of the three countries that went on to form the first East African Community, Uganda’s Dr Milton Obote was 38 in 1963 and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere 41. Kenyatta was the elder one by decades. Both Uganda and Tanzania had attained independence before Kenya.

By later African standards, Kenyatta didn’t last long in power as a strong founding father. He passed on at 81 on August 22, 1978, after 15 years as the Big Man.

Kenyatta looks and is described as old in the photographs and in descriptions. Perhaps it was the times. Wealth advances in medicine, grooming and hair dye hadn’t spread the way they have today. But he was younger than the oldest African president today—Cameroon’s Paul Biya, who is 89 and has been president for 41 years now.

On Monday, Bola Ahmed Tinubu was sworn in as Nigeria’s president following elections in February. Tinubu is 71—five years older than Kenyatta was when he became Prime Minister in 1963. Tinubu is the youngest of the 10 oldest serving African presidents, whose average age is 80.

However, at his swearing-in, Tinubu looked in bad shape. He struggled to walk, had to have a pen pressed in his hand and was helped to sign swearing-in paperwork.

If in 1963 Kenyatta was among the very few outliers in terms of age in Africa, today he wouldn’t be. If African “democracies” like Ghana and Nigeria teach us anything, it is that electoral politics favours older presidents.

There will be a lot of flowery talk about a young Africa, how it’s time for the continent’s youth to rise and shine, but when the ballot is cast, the victor will not be a bright-eyed 38-year-old politician with most of their life ahead of them.

Most young leaders in Africa have come to power initially by going to the bush to fight a guerrilla war or seizing government in a military coup—as leaders like Lt-Col Mamady Doumbouya in Guinea and Captain Ibrahim Traore in Burkina Faso have done in recent times.

Accumulate money

Why does democratic fortune favour older African politicians? The obvious first reason is money. If you have been around for long, you will also have had a greater opportunity to establish the networks and accumulate the money necessary to secure victory in our graft-ridden elections.

You are also likely to be more known at the grassroots; a 65-year-old presidential candidate will have served as a government district officer (District Commissioner, Health officer, agricultural officer, Education officer, et cetera) in half of the country (possibly leaving behind children with various concubines in all those places).

He will have done favours, bought beers and helped local potentates to steal land from their folks in all those areas. A newbie, 15 years out of college, just cannot compete against that—except on Facebook and Instagram.

However, it also seems that African voters are involved in very complex political arbitrage in electing older candidates in the majority of countries. The case of both Tinubu and his predecessor, Gen Muhammadu Buhari, points us to the calculations that might be going on.

Too many African leaders tend to cling to power for too long, and many have cajoled and bulldozed to change constitutions to remove term- and age limits so that they can rule for life—as Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni, in office for 37 years so far, has done.

Electing a 71-year-old Tinubu ensures that, even with the best of health and effort, if he were to change the constitution and bribe his way through, he wouldn’t rule for more than 20 years.

An older shaky-handed big man who dozes off half the time is also likely to have a weak grip and an incompetent government, with various factions contending for supremacy.

A dictatorship that creates wiggle room and fluid spaces where a degree of freedom exists and can be exploited by progressive forces.

By contrast, if you have a 30-year-old who hits the gym, thus in good health and doesn’t have to spend a quarter of the year in London hospitals, as Buhari did in Nigeria, you could be in trouble. You end with an autocrat like Equatorial Guinea’s President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has been in power for 44 years.

Ironically, once a big man manages to stay in power for 30 years, things get better for him. The voters are likelier to keep him in office, expecting he will die off soon than elect a baby-faced successor.

As the young people say, fear the African voter.

—- Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. @cobbo3